Consider: A class of people obsessed with being seen to eat the “in” foods; crazy food fads embraced across all classes; restaurants run by celebrity chefs, food writing that turns eating into an art form, an obsession with local and seasonal food, science and technology colluding to create superfoods, an underclass subsisting on a diet based on sugar. Is this a perfect summary of today’s obsession with food?

Nope, this is Edwardian Britain.

As a brief respite from cookie recipes and the like, for the month of January, I’ll be sending out potted histories—tastes, if you will—of the weird world of Edwardian and Progressive era food and diet culture. A culture that you’ll see has many similarities to now.

Start the new year right and help a friendly algorithm. Please click the “like” heart above.

A food revolution began in the late Victorian period in Britain, with none other than the Prince of Wales at its center. Renowned for his 4,000 calorie diet, 30-course breakfasts and a roast chicken on his bedside in case he became peckish in the night, the future King Edward VII’s nickname was ‘Tum-Tum.’ ‘Tum-Tum’ made dining out in restaurants an acceptable pastime, which gave rise to the first celebrity chefs.

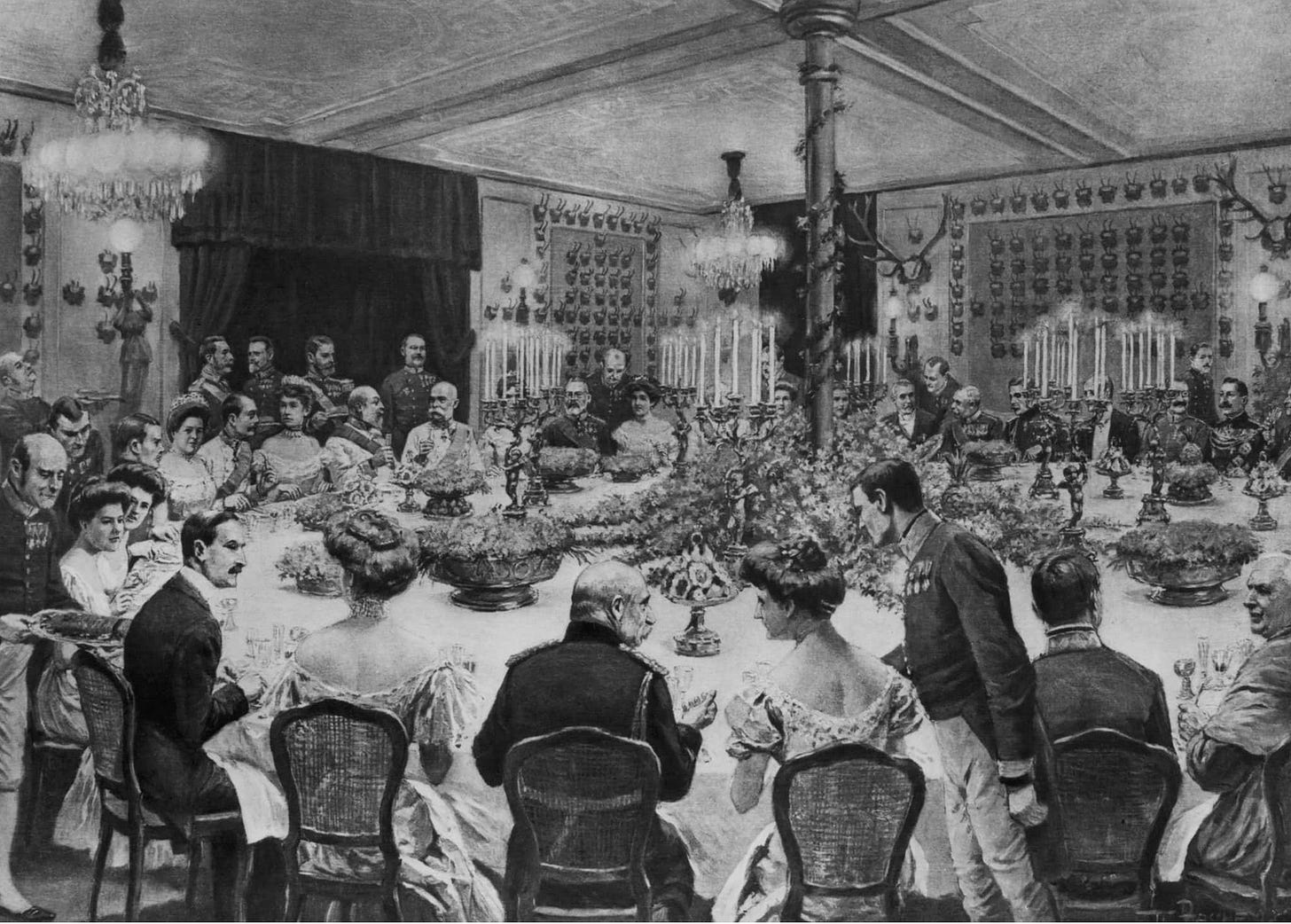

The upper classes embraced the excess. Edward spent weekends flitting to and from fancy country estates, where hosts would refurbish their homes in preparation for his arrival and spend the equivalent of $20,000 on meals literally fit for the King. (We shall talk about his sexual escapades another time.) Meanwhile, the poor lined up at the backdoor of the manor house kitchen to buy drippings to smear on bread for dinner.

For many middle and upper class Britons at the turn of the twentieth century, religion took a backseat to a growing movement that blended science with the spiritual to inform how they lived. The well-to-do embraced food fads that all appeared to be based on some sort of science, including the “knowledge” that oysters could cure gout and impotence. The middle and upper classes embraced a diet fad called Fletcherism that required diners to be silent as food was masticated until it turned to liquid. Women held “Muncheons” and “Chew-Chew Clubs” in restaurants. At the same time, low-carb diets were first popularized and all-yogurt menus gained attention. Entire pamphlets were devoted to decoding food dreams (Dream of beetroot? Disgrace is sure to come your way.).

New discoveries in science and technology—among them an understanding of calories, vitamins and improved methods for canning-- gave social reformers new reasons to believe they could improve the quality of life for the legions of poor and malnourished. George Orwell wrote of the “troglodytes” that inhabited every street. While there had been talk of reform dating back to the 1830s, the government had no choice but to take notice when Boer War conscription was impacted by a stunted unfit group of possible soldiers. The minimum height for soldiers had to be lowered to 5 feet in order to ensure a large enough infantry.

Consumer culture was also expanding: Many of the most iconic British brands were born in the early part of the century. Industrialized canned goods became more affordable—and less full of adulterants then a half-century earlier. Social reformers embraced these with open arms: Now there could be inexpensive food available to everyone.

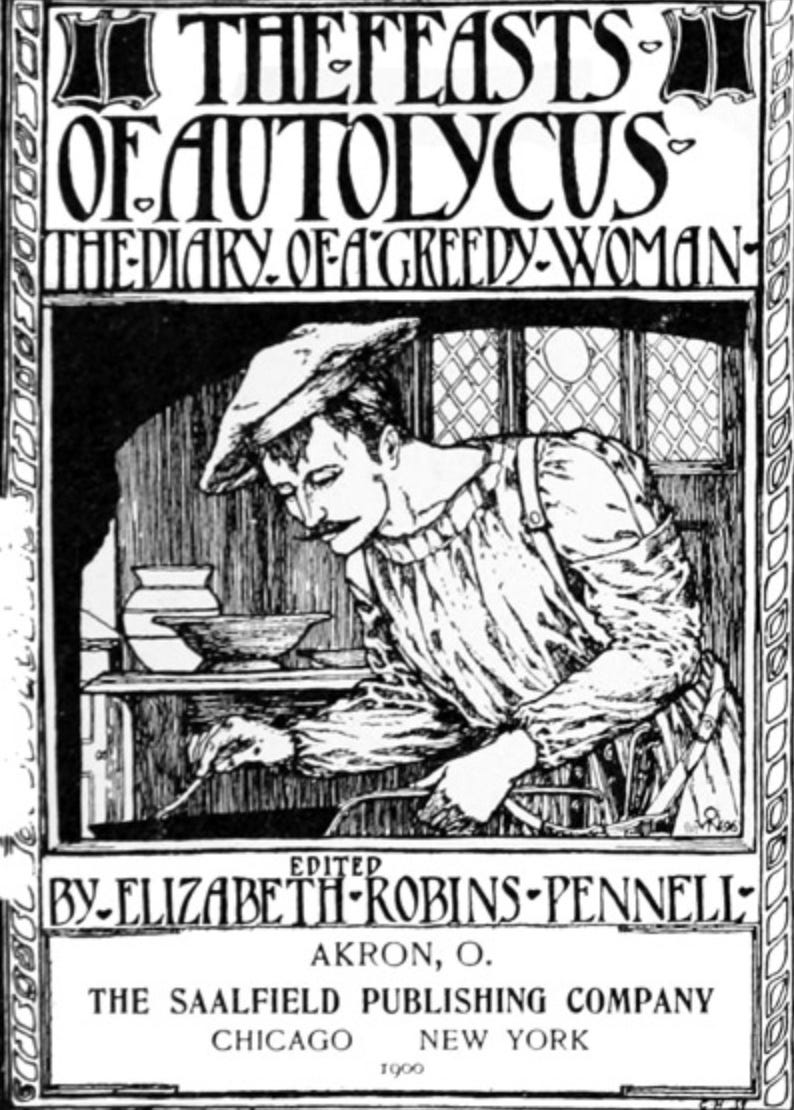

At the same time, while Edward and his posh set concerned themselves with how many ortolans stuffed with foie gras they could roast for dinner that night, the Aesthetes, led by writer Elizabeth Robins Pennell, devoted themselves to the idea that food was more than mere nourishment and raised food and cooking to an art form. Pennell is considered the first modern food writer, and wrote rhapsodically on the subject of meals, with passionate enjoinders to eat seasonally and with respect for ingredients. Pennell paved the way for future writers such as MFK Fisher and today’s band of foodies

Pennell saw the act of eating as one to be —shock, horror—enjoyed by all, but especially women. Pennell was a far cry from the stodgy and sensible ideal of English food at the time, Mrs. Beeton, as she gleefully exhorted readers to relish food. This self-professed “greedy woman” turned the kitchen and dining room into modern holy spaces: “Gluttony is ranked with the deadly sins; it should be honored among the cardinal virtues.” It doesn’t quite have the ring of the today’s cocktail napkin motto “Life is short, eat dessert first,” but it certainly makes a vivid point.

This manic period of change was brief. King Tum-Tum died in 1910, and the war that would turn Britain and the world upside-down was just a few years in the future.

George Orwell sums up the mood of the era in “Such, Such Were the Joys”:

“From the whole decade before 1914 there seems to breathe forth a smell of the more vulgar, un-grown-up kind of luxury, a smell of brilliantine and créme-de-menthe and soft centred chocolates – an atmosphere, as it were, of eating everlasting strawberry ices on green lawns to the tune of the Eton Boating Song. The extraordinary thing was the way in which everyone took it for granted that this oozing, bulging wealth of the English upper-middle classes would last for ever, and was part of the order of things. After 1918 it was never quite the same again. Snobbishness and expensive habits came back, certainly, but they were self-conscious and on the defensive. Before the war the worship of money was entirely unreflecting and untroubled by any pang of conscience. The goodness of money was as unmistakable as the goodness of health or beauty, and a glittering car, a title or a horde of servants was mixed up in people's minds with the idea of actual moral virtue.”

(You can read “Such, Such Were the Joys” in its entirety here.)

I hope you enjoyed this wee glimpse into this period. I truly have pages of notes on the subject, so narrowing it all down was hard. I think I was encouraged this week watching my son whittle down college essay attempts from 700 words to 250. Much gets left on the kitchen floor.

And, of course I’ll have some recipes for you this month. I haven’t been overtaken by aliens. Cats maybe, but not aliens

.

This substack is a reader-supported publication. I cannot do it without you. If you’re able, paying for a subscription helps pay for the groceries necessary for recipe-testing and recipe development. Also, it supports me—a freelance writer—and ad-free journalism. And starting this month, subscribers will receive special recipes and posts only available to them.

The pay scale for journalists and writers has not kept up with the cost of living. That’s why having a substack newsletter has become such a terrific venue for so many writers. Best of all, it puts me, Bosco, Calvin and Clyde in touch with our readers like never before. And lets me put my history degree to good use. Thank you.

Can’t afford a subscription? Do the next best thing and give free subscriptions to all your friends. The more the merrier. And now, there’s a discount for subscriptions.

Many in our billionaire class still equate money with virtue, intelligence, and morality, it seldom does.

This was fascinating. More! More! xo