Just a quick note to apologize for a lack of newsletters over the past few days. I’ve been dealing with a family emergency, which has kept me from home, kitchen and computer.

Until I get into the kitchen again (I am hopeful it’s later this week!), I leave you with a bit of a book idea I’ve been working on about the history of the American kitchen.

I’d love to know your thoughts and reminiscences about the kitchen you grew up in. Please leave them in the comments below.

PS: 34 counts!

How America’s Kitchens Changed the World

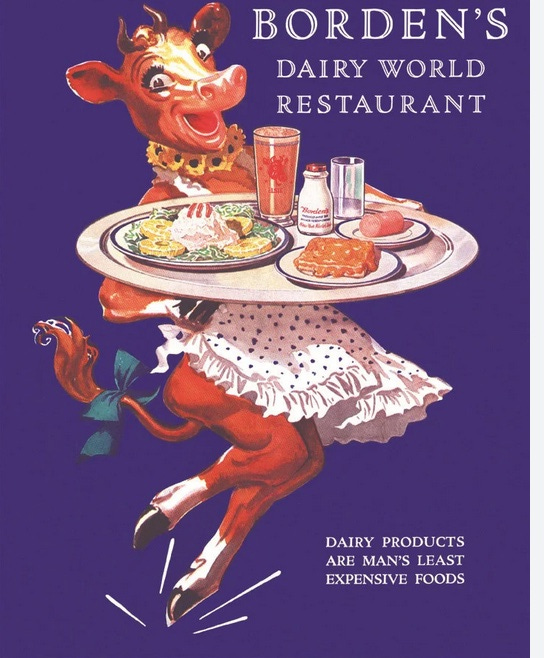

My mother Carol had two memories of visiting the 1939 World’s Fair as a child, and both involved eating. The first was the chocolate float from Borden’s Dairy World that got larger every time my mother described it. The second was her visit to the Kitchen of Tomorrow, where she was amazed by a sleek kitchen—all steel, glass and plastic—with appliances powered by electricity. It was a far cry from her family’s New York City apartment kitchen, where the stove’s hissing gas burners and exposed-flame broilers scared her so much that she referred to it as “The Dragon.”

Westinghouse devoted an entire pavilion to the wonders of electricity—and the appliances that would make stoves like my mother’s Dragon extinct. The exhibits showcased magical appliances that would make dinner at the push of a button and then clean themselves. While 44 percent of Americans had electric “ice boxes” by 1940, many of them—especially those in rural parts of the country—had only just gotten reliable electricity in their homes, which made the Westinghouse exhibit even more incredible to the Fair’s millions of visitors.

In that pavilion, nine-year-old Carol, along with thousands of others, watched women in bathing suits and high heels cook fried eggs over a magnetic (induction) stove without splattering hot oil on their exposed legs. In Westinghouse’s “The Battle of the Centuries” tableau, an actress playing “Mrs. Modern” raced “Mrs. Drudge” to see who could wash dishes faster. Forty times a day, poor Mrs. Drudge, in her dowdy white apron, scrubbed each filthy dish by hand, while splashing hot, soapy water all over herself and the floor, and brushing sweat-matted curls from her eyes. Mrs. Modern—with her perfectly coiffed hair, crisp floral frock and stylish spectator pumps (no apron necessary!)—spent much of her time perched on a modern steel stool while her dishes were cleaned by a Westinghouse dishwashing machine.

The lovely Mrs. Modern popped up at many of the fair’s exhibits, including Westinghouse’s “Hall of Electrical Living,” which among other amazements, included a robot named “Elektro, the Moto-man” that could handle 26 household tasks, and promised “the release of women from bondage and drudgery through electricity.” If Mrs. Modern didn’t want this 7-foot-tall gold behemoth in her house (it’s skills included smoking a cigarette and blowing up balloons—talents that made him about as helpful around the house as her husband), she could simply load up on Westinghouse’s many shiny new appliances that could, the emcee declared, cut her time doing chores in half. And if Mr. Modern brought the boss home at a moment’s notice, fear not: Her radiating oven could cook a roast in minutes rather than hours, and an angel food cake could mix and bake itself, which left “the Mrs.” plenty of time to spruce up before cocktail hour.

All this wasn’t just a pitch for innovation; it was a call for a soft revolution. The message was clear: the apron-strings were being cut, and women were now in charge of their future. Liberation was promised to my mother and millions of other girls and women, thanks to the wonders of technology. Getting the vote was great, but nothing beats a dishwasher. A Westinghouse ad from that year offered a chirpy message of hope: “It’s fun—when you let electricity work for you.” Sponsors and exhibitors across the fair delivered a similar promise: We will transform your life into one of ease.

And they did deliver on that promise… sorta. The 1940s kicked off an astounding arms race in kitchen technology that slowly but steadily transformed what was traditionally viewed as the “woman’s place” into the sexiest room in any modern American home. I describe it that way to acknowledge all the gleaming technology on display there, but also to address one of the best quotes from the Women’s Lib movement of the ‘60s. In The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan called the kitchen a repressive space, and noted that, “No woman gets an orgasm from shining the kitchen floor.” That’s almost certainly true, but a few of my friends admit to feeling a little aroused the first time they watched a Roomba clean up a spill on their linoleum.

Claiming that a self-defrosting refrigerator and an electric pressure cooker are as important as closing the gender pay-gap is hyperbolic, but it is not a lie. The transformation of kitchens from sweaty, greasy pits of drudgery into sleek, shining and often astounding miracles of technology (microwave, anyone?) hasn’t gotten all women out of the kitchen, but it has given them more time, more control, and more satisfaction. And just as important for American families: All this has gotten more men, and more children (and even dinner guests) into the kitchen.

Today, the kitchen is more than where we make dinner; it is where we make America. All of American culture has passed through the kitchen, checked out what’s in the fridge, and taken a seat at the kitchen table. The kitchen is the repository for our collective national experience as much as our personal histories: It’s who we are and, more important, it’s who we aspire to be.

I’m the youngest of seven. We were a big farm family so lots of meat, potatoes, garden vegetables, and fresh milk. We had a wood cook stove but rarely did we do more than keep a stew or soup at a slow simmer. Most of the cooking was done on our electric oven. We had a yellow glass cookie jar that always had cookies, a never ending supply! I don’t know if it’s genetics or the food I grew up consuming, but I never get sick. (Let me touch wood on that one.) I don’t get colds or the flu. I work in a hospital and I’m one of the few who never got COVID-19. I’m 56 now and take zero medication. I also still live in the farmhouse I grew up in and the kitchen has never been remodeled. Although we had to remove the heavy cast iron wood cook stove because it was threatening to crash through the floor into the basement.

My grandmother had a chrome & vinyl telephone chair with a pull out step stool in her kitchen. If the rotary phone rang, she could sit on the chair and talk while watching what was in progress on the stove or in the oven. It served double duty as a ladder to the higher cabinets where she kept all of her best linens, baking pans and more. I miss that chair.