Freedom from Drudgery Can Be Yours!

This week's kitchen history: The early science of housekeeping. Plus, a contest!

Today’s post is a snippet of American kitchen history and is the second in what will be a regular feature of this substack going forward. I’ve meant since I launched the newsletter way back in 2020 (!!!), for food and kitchen history tobe as much a part of the newsletter as recipes. So, sound the trumpets, make a batch of old-fashioned coconut shortbead or the Macaroon Mound pictured below, and settle in for a read about Christine Fredericks, the Henry Ford of the kitchen.

Would you please click the like button above to make the Algorithm Monster happy?

Christine Frederick stood over a sink of grimy dishes in the kitchen of her Long Island home counting silverware, plates and glasses sometime around 1912. After an evening meal she found herself facing down a pile of 48 pieces of china, twenty-two pieces of cutlery and 10 cooking pots and utensils.

Mrs. Frederick was not your ordinary housewife. She was one of the leading efficiency scientists of the early 20th century, and with near-religious fervor, promised to liberate housewives from drudgery and make their time doing housework more productive. Inspired by Henry Ford and his new automobile assembly line, she applied similar techniques to the act of dishwashing.

First, she changed her drainboard from the right- to left-hand side of her sink, and then with engineering precision, she began to wash the dishes:

“I pick up a plate with my left hand, scour it with the cloth held in the right hand, and lay the plate on the tray with my left hand, without changing hands or passing my left arm across my right arm. My left hand is capable of repeating the “laying-down motion” very fast and very easily, while the right hand never drops the cloth, but scours one dish after another rapidly.”

By Mrs. Frederick’s calculations, use of her dish-washing technique could eliminate drying three acres-worth of dishes a year, and save 90 minutes of housework time a day.

Mrs. Frederick was part of the scientific management movement known as “Taylorism.” Frederick W. Taylor, a mechanical engineer, stopwatch in hand wherever he went, analyzed workplaces to find the most efficient way to complete a task. Every step saved, every motion modified for ease and efficiency could benefit the worker and would definitely benefit the factory owner. Taylor’s goal was to ensure American industry prospered, and one of his clients, Henry Ford, surely did. Thanks to the time-motion studies done by “Speedy Taylor,” as he was known, Ford’s assembly line purred along: Car manufacture at the Highland Park plant went from a 12-hour process down to a measly 1 hour 33 minutes start to finish.

The Second Industrial Revolution and The Progressives

These time-motion experiments began with the Second Industrial Revolution. A quick history refresher: The first Industrial Revolution began in the late-eighteenth century and slowly shifted society away from an agrarian focus to an urban one. Prior to this, a woman on a farm, say, in central Massachusetts might have to spin and weave her own cloth, but the Industrial Revolution made low-cost mass-produced goods available. She also might leave the bleak future of farm life behind her and move to a mill town, such as Lowell, and start work in one of the cloth-making factories, where she’d work even longer hours than on the farm, and go on strike for better wages.

Similarly, the Second Industrial Revolution, in the early twentieth century, saw new job opportunities for men and women and the introduction to daily life of electricity, cars and important household machines that upended daily existence for many. Much of the technological innovations that occurred still impact our lives today, and include the refrigerator, electric iron, dishwasher, vacuum cleaner and my personal favorite, the toaster. Advancements in science and medicine, the rise of nutrition science and home economics, plus exponential growth of mass-market processed food (Jell-o! Velveeta! Ritz Crackers! Oreos! Marshmallow Fluff!) would transform daily life. The implications of these changes on the role and experience of women over the next hundred years would be monumental.

Progressive-based movements led by social reformers, home economists, scientists and architects began in the late 1890s, centered around suffrage, nutrition, health and child-rearing. Their efforts brought new attention to the role women could – and some would insist should -- take in society, and played an important part in changing attitudes towards housework.

The Progressive housekeeping movement was directed squarely at the white middle class. Reformers saw the “professionalization” of everyday activities by housewives as key to change. Theirs was a simple and direct message that was spread from church to ladies’ magazine to the National Congress of Mothers (the precursor to the PTA) and to advertising: Women were in charge of the house. Domesticity was a virtue. Middle-class and upper-class white women were encouraged to use their privilege and position (and newly found free time) to help those less fortunate. Housewives were motivated to address the most pressing needs of society, among them poverty, child labor, women’s work, and to a lesser extent (but no less worthy in their eyes), the “need” to Americanize new immigrants.

Efficiency experts such as Mrs. Frederick were dedicated to the cause and spread the word through magazines, speeches to women’s clubs and by appearing as a spokeswoman in advertisements for home goods. The main pulpit for Mrs. Frederick’s message was Ladies Home Journal magazine, where her housekeeping column began appearing in 1912. At the time, the Ladies Home Journal was the most widely read magazine in the United States, with one million subscriptions in 1903. (It was popular not only with women, but with men: It was the third most requested magazine by soldiers during World War I.) Both Mrs. Frederick and advertisers realized the power of her reach, and soon she was testing newfangled household equipment in her country home, where she turned her actual kitchen into a test kitchen and received regular deliveries of the latest stoves and other household equipment for trial. She became a one-woman Good Housekeeping Institute (Good Housekeeping magazine’s own testing division had started in 1900).

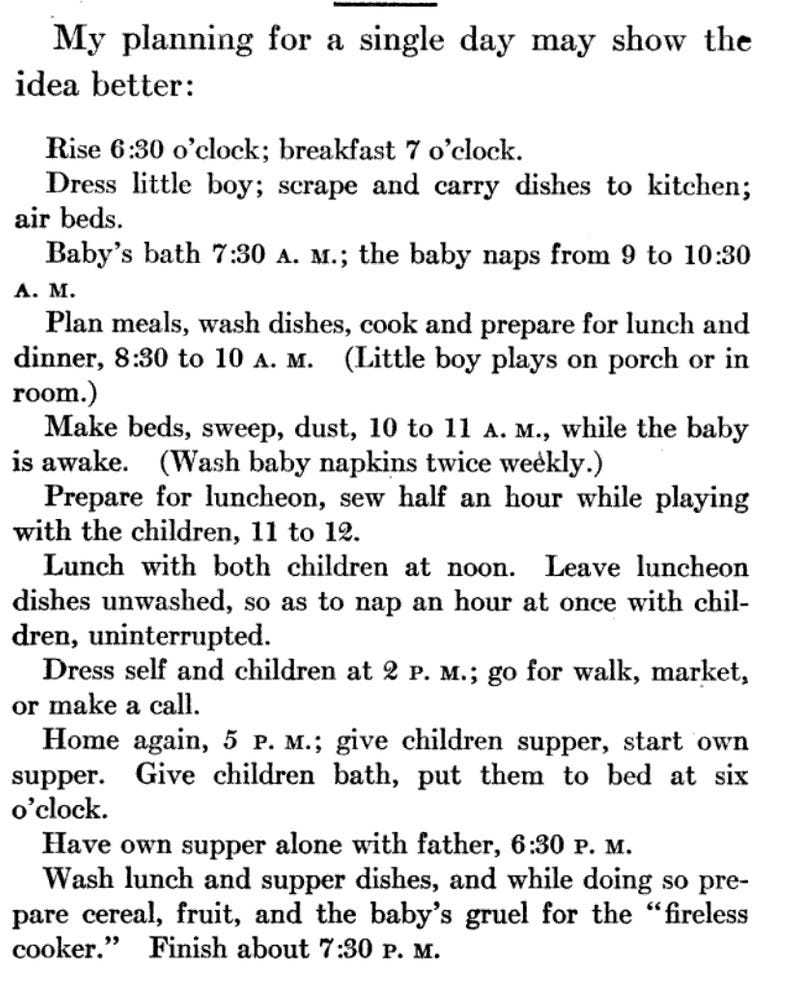

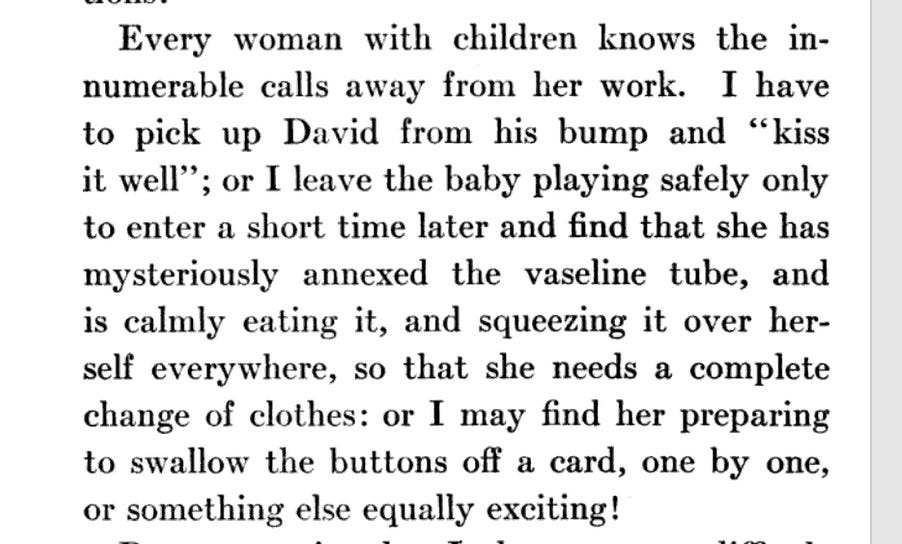

Mrs. Frederick’s home-motion studies of women as they cooked, served food and washed dishes inspired new ideas in kitchen design detailed in her popular book published in 1913, The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management. With efficiency as the beacon of light shining into the dark, dank drudgery of housewifery, she focused her attention on improving the “fundamental” daily steps of cooking and cleaning: By shopping for modern kitchen equipment, they could help themselves and the American economy. Frederick’s message was clear in her book and her Ladies Home Journal columns: Do your part as consumer, and freedom from drudgery can be yours.

CONTEST!

Without looking them up (honor code!), can you guess the order in which these industrial food products appeared on the market, from earliest to latest? The first three people to answer correctly will get free year-long subscriptions to the substack for themselves or a friend! DM me your answers.

Jell-o

Velveeta

Ritz Crackers

Oreos

Marshmallow Fluff

Let me know what aspects of kitchen life and history you’d like to know more about. And tell me, what do you find full of drudgery?

Could you say no to the grizzled face below?

This substack is a reader-supported publication. If you’re able, paying for a subscription helps keep Bosco in pizza bones and is pays for recipe testing and other groceries necessary for recipe-testing and recipe development. Also, it supports me—a freelance writer. The pay scale for journalists and writers has not kept up with the cost of living. That’s why having a substack newsletter has become such a terrific venue for so many writers. Best of all, however, it puts me, Bosco, Calvin and Clyde in touch with our readers like never before. Thank you.

Can’t afford a subscription? Do the next best thing and give free subscriptions to all your friends. The more the merrier.

Eeeeeeeeegads! The woman's schedule!

I find this kind of stuff fascinating (and makes me grateful it's waaaaaay in our rear view mirror). A great source of info is your state land grant university's archives. Betty Crocker was an alum of ours and there are some really fun pictures of her and stories about her research. Many state 4-H programs have info as well as Extension Home Economics groups (if those still exist).

Thanks for the fun peek into history, Marissa!