A 'Minor Memorandum'

My dad's recollections of Kristallnacht, November 9 and 10, 1938

“In order to have faith in our quality as human beings, we need to remember!”

This morning on Threads, I saw a video of a college student at Concordia University in Canada, shouting the “K” word (rhymes with “bike”) at a fellow student after a teach-in that appears not as effective as maybe hoped.

Today is also the anniversary of Kristallnacht, the two days of coordinated attacks by Nazis and their friends on Jewish people, November 9 and 10, 1938. Storefronts of Jewish businesses were smashed and the insides looted, synagogues burned, Jewish men were rounded up. It was a general Nazi free-for-all, with the Jews the focus. The pretext for the pogrom was the assassination of high-ranking Nazi Ernst von Rath by a 17-year-old Polish-Jewish refugee, Hershel Gruenspan, who desperately wanted to bring attention to his family’s deportation from Germany to Poland.

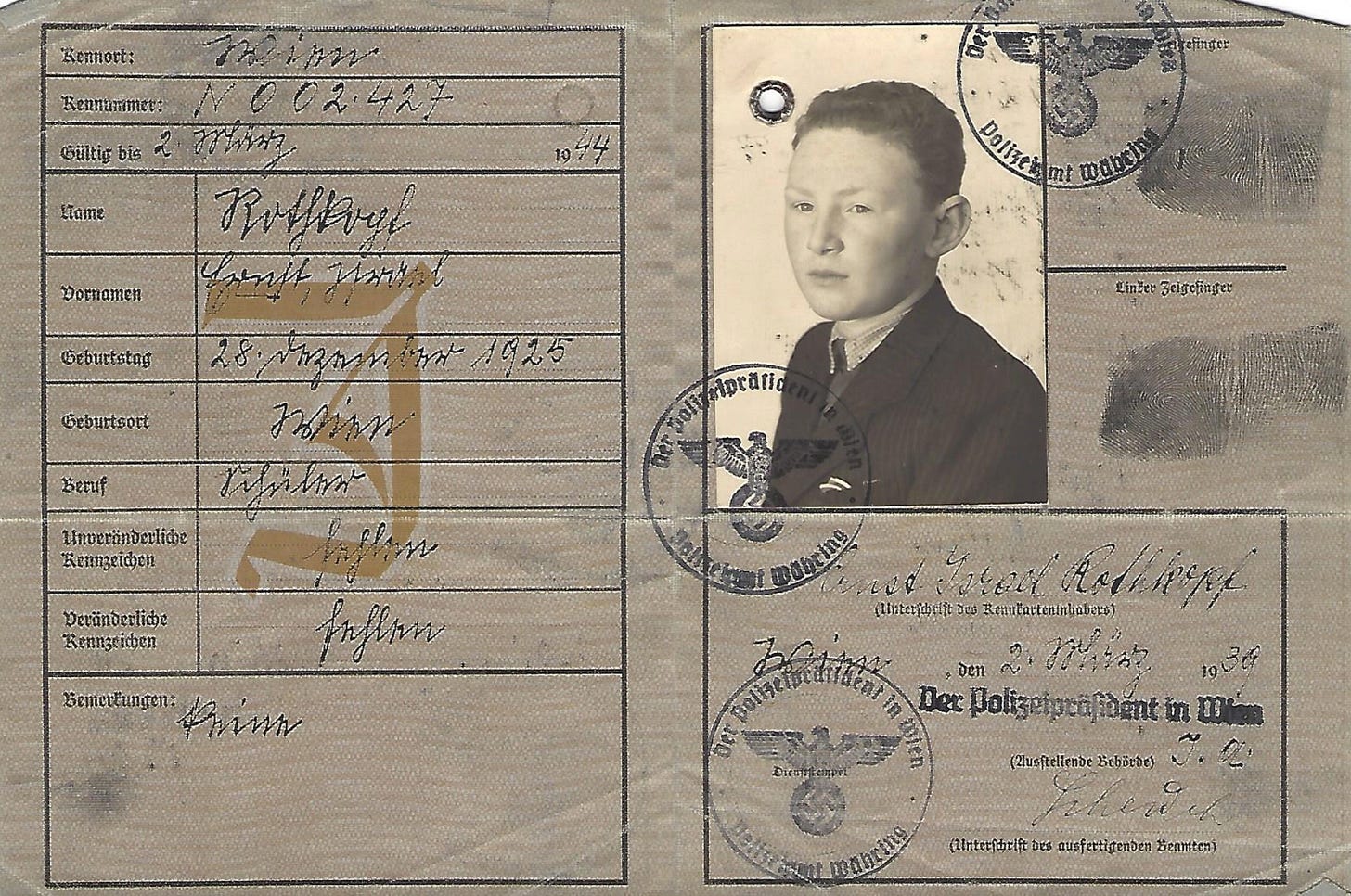

My father was a 12-year-old kid in Vienna on November 9, 1938. He lived there with his parents in a small one-bedroom apartment on the Ottakringstrasse. On the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht, I was at college and found in my mailbox a manila envelope addressed to me from my dad. Inside was a typed recollection of the events of Kristallnacht.

It’s important to note my father barely ever spoke about what life was like for him and his family, save for occasional fond memories, such as spending summers in a Fahrafeld, a small mountain village with his Great Aunt Pepe (Josephine), and how after she would make raspberry syrup, the pink-stained cheesecloth would blow in the breeze on the clothesline. So, to receive this letter in the mail, “a minor memorandum” as he called it in his typical way, was a big deal.

Over the years I’ve shared it with my kids’ teachers who were teaching a unit on the Holocaust, in the hopes it could tie what feels like a distant historical event to actual kids in the classroom whose “Poppa” lived through it. One can only try.

So, here we are again, 85 years later, antisemitism, Islamophobia and religious hate is peaking again. Jewish students at the University of Massachusetts have been told not to walk alone on campus, after a fellow Jewish student was attacked. A young boy is killed and his mother is wounded after their landlord stabs them for being Muslim. I’ve always felt this sort of hate was always bubbling under the surface. I just hoped this time, more people would speak out against it.

So, today’s post isn’t about cookies, although my father would think that was a damn shame, because he loved cookies. (It should surprise no one how I ended up, a real Daddy’s Girl, making sure the world was filled with as many cookie recipes as possible.)

For the moment though, I’ve reprinted below the letter my dad sent my brothers and me about Kristallnacht. (NB: He spells it ‘krystallnacht,’ something his editor wife and daughter couldn’t get him not to do.) And yes, if you detect some wry humor at times, you’re correct. That’s just how we Rothkopfs roll.

A Minor Memorandum to My Children on the 50th Anniversary of Krystallnacht

(November 9, 1988)

I don’t intend to make this a big deal literary effort or a weepy emotional debauch. I simply want to tell you what I remember about Krystallnacht. So you should remember as well. And if there are to be others like us, so you can tell them. Nothing big! Just a small and portable lesson about the planet we live on and the hazards of being a little different.

Krystallnacht did not start for me until November 10, 1938. I knew that von Rath had been shot by Gruenspan but I knew nothing about what was happening all over Germany during the night of the ninth. I was 12 years (12 10/12 ths )old and I was asleep.

I was still lying in my bed, at about seven on the morning of November 10, when there was loud knocking on our door. I heard my father and mother (your grandparents ) talking to some people. Several Stormtroopers (SA) had come to arrest Jewish men. The entrance to our apartment was through the kitchen and all this was taking place in the kitchen. After a few minutes I heard one of the Brownshirts ask whether there were any other male Jews in the apartment. Grandma said only my little boy. I don’t think they believed her because they came into our main room, where my bed was. I closed my eyes and pretended I was asleep. They came to my bed and they looked at me and they must have decided either that I was too young, or that I looked too fierce to mess around with since there were only six of them. So they took just grandpa with them and they left.

As we later found out, they took grandpa to the local police station. From there they marched him and others to the Rossauer Kaserne, a military barracks. He was lucky because he had a roof over his head. Many other Jewish men were taken to a large soccer stadium and did not have a roof over their head.

Grandpa had been fired from his regular job as a bristle processor a couple months before. He was earning some money by helping a carter hauling the furniture of Jews that had been kicked out of their apartments. The cart was pulled by one brown horse. Grandpa had a job scheduled for that morning.

Grandma sent me to help the carter in grandpa’s place. Maybe grandma was a tough Hungarian cookie who did not want the Rothkopf’s reputation as men of their word sullied, or maybe we needed the money, or perhaps she wanted me out of her hair so that she and Aunt Mitzi ( who lived in the next apartment and whose son Walter and friend Albert were already on the way to Dachau) could weep in peace.

I don’t remember exactly where I met the carter but it was at his client’s apartment near the Jewish section of Vienna. We loaded the wagon with furniture. I sat next to the driver on the high bench behind the horse. Then the brown horse slowly pulled us through the streets towards the place where we had to make our delivery.

Groups of people were standing in front of the broken windows of Jewish stores, gawking while Brownshirts were putting their owners through their paces — handing over business papers, washing the sidewalk with lye, licking Aryan employees shoes clean. Anything that would keep the cultured Viennese crowds amused. We passed a narrow street that led to one of Vienna’s larger synagogue. The alley was jammed with jeering onlookers. Stormtroopers were throwing furniture and Torah scrolls through the big main door into the street. One side of the roof (I couldn’t see the other and you know what a skeptic I am ) was afire. I remember very vividly the twists of whitish-yellow smoke that were curling up the slope of blue tiles.

Farther on we passed another synagogue that was fully ablaze. The police had made people stand back from it. I suppose they feared for their safety. A fire truck was parked down the street. The firemen were leaning against their equipment, talking and smoking cigarettes. Everywhere there were clusters of people, in a holiday mood, gathering around smashed Jewish stores. Little groups of Jews, both men and women, were being led along the sidewalk flanked by squads of SA men. The Jews were made to do all sorts of menial chores. Someone told me later, that one elderly Jew asked to go to the toilet. They made him go in a bucket and then forced him to eat his feces.

By now I was beginning to figure out what was going on. I sat high on my horsey throne (just like the Duke of Edinburgh when he drives his high-stepping pair, except that I didn’t wear an apron ). Whenever we passed a sidewalk event or other happening, I pulled down the wings of my nostrils (I thought I looked more Christian that way), staring straight ahead, but watching the Nazi street theater out of the corners of my eyes. The driver, who was also Jewish, was a hard old soul. I don’t remember him saying a single word to me, all day, about what was going on. Maybe he thought I was too young to hear about such things.

I don’t remember much more detail. I got paid. The trolley I went home on was crowded. I kept staring out the window so that people wouldn’t notice the handsome Jewishness of my face. Beyond the rattling trolley panes, the peculiar happenings of November 10, 1938 were still in progress here and there, even as the day’s light was fading.

When I got home, grandma and Mitzi were still weeping. They had just come back from the police station but grandpa and the other Jews were no longer there.

Grandpa came home ten days later. He had spent that time in a room with 500 other people and one water faucet. They did a lot of military drill ( was this the beginning of the Haganah?) and exercises — push-ups, deep kneebends, and the like. Some who didn’t do so well got beaten up. He never told me whether they did anything to him. But then I wouldn’t tell you either. Grandpa was lucky. A lot of the Jewish men who were arrested on the 9th and 10th of November were sent to the concentration camp at Dachau.

Not one single synagogue was left intact in all of Vienna. That really screwed me up because I was nearly thirteen. You need to have a Torah to become a Bar Mitzvah and you need to have a table on which to lay the scroll while you read. And how was I to get a fountain pen now?

The dead, of course, are dead. They are mourned by those who remember. Tears dry. Bruises heal. Razed synagogues become parking lots. Injured dignity heals although slowly. What hurts most to this day is impotent compassion for those who were swept away.

In order to have faith in our quality as human beings, we need to remember! And that’s why I am writing you this note.

Want to make some cookies? Here’s the recipe for my dad’s favorite biscotti.

Thanks for reading this far and for allowing me to share this note. Feel free to share it.

Marissa Rothkopf-Bakes: The Secret Life of Cookies is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Thank you for this. I lived in Germany, as a high school student. We took a field trip to Dachau and, eventually, Auschwitz-Birkenau. I'm not sure if it was my imagination or some sort of spiritual connection but it was as if I could feel agony, particularly in the showers and crematoriums. I was 16. I had to leave and wait on the bus because it was so overwhelming. As an adult, I worked at the State Department, here in DC. Before the Holocaust Museum opened, they had a display in the front lobby of where I worked. They had blown up photos of life, in concentration camps, to life size. It was very visceral, walking through there every day, seeing these photos so up close and personal. So now, seeing the hatred and idiocy again just makes me mad and proves to me that time is cyclical rather than linear. And I'm doing what I can to fight against hate.

My family was lucky. Both sides of grandparents left Russia (what is now Ukraine) before the turn of the 20th century. But we were taught the horrors of the Holocaust. Many of my childhood friends had parents whose forearms bared their concentration camp tattoos. We have always said, "Never again" and believed it. I no longer believe it. Any society that can elect the likes of Trump, Gaetz, Greene, Jordan, can be easily led down that path. They need someone to blame for the struggles in their lives- conveniently forgetting that we all have struggles. Thank you for sharing your father's very poignant words, and of course for honoring his love of cookies.